Practice Update Feb 2020

Ian Campbell • 24 February 2020

P r a c t i c e U p d a t e

January/February 2020

Lifestyle assets continue to be an ATO audit target

The ATO has revealed it will request a further five years’ worth of policy information from over 30 insurance companies about taxpayers who own marine vessels, thoroughbred horses, fine art, high-value motor vehicles and aircraft.

The ATO expects to receive information about assets owned by around 350,000 taxpayers from 2016 to 2020 as part of its data-matching program.

This information (provided by insurers) is intended to be used by the ATO as part of its compliance profiling activities.

For example, ATO Deputy Commissioner Deborah Jenkins said:

“If a taxpayer is reporting a taxable income of $70,000 to us but we know they own a three million dollar yacht then this is likely to raise some red flags.”

She clarified that the data will not be used to initiate automated compliance activity.

“Taxpayers selected for compliance activities are identified through other methodologies. The data is made available to our compliance teams to support their risk profiling of the selected taxpayers. Existence of an insurance policy may or may not prompt the compliance officer to pursue a particular line of enquiry.”

Aside from helping identify taxpayers who may be understating their income, the data from insurers may be used by the ATO to identify taxpayers who have made capital gains on the disposal of certain assets but who have not declared this to the ATO.

It will also be used by the ATO to identify incorrect claims for GST input tax credits where taxpayers are incorrectly claiming GST credits as if the (private) item was a business asset.

Additionally, SMSFs the ATO suspects may be acquiring lifestyle assets purely for the personal enjoyment of the fund's trustee or beneficiaries are also likely to be looked at by the ATO.

Insurers are required to provide the ATO with policy information where the value of assets is equal to or exceeds the following thresholds:

- Marine vessels $100,000

- Motor vehicles $65,000

- Thoroughbred horses $65,000

- Fine art $100,000 per item

- Aircraft $150,000

Editor: If you feel that you may be targeted by this latest ATO data collection activity and are concerned about the implications, please feel free to contact our office to discuss your individual circumstances.

Ref: ATO website, 18 December 2019

Disclosure of business tax debts – Declaration made

Following the enactment of legislation in late 2019, the ATO can disclose certain business tax debt information to external credit reporting bureaus.

This information will primarily be used when issuing external creditworthiness reports in relation to relevant businesses, effectively treating tax debts in a similar manner to other business debts.

More recently, the Government issued a Declaration to determine exactly what class of entities may be subject to such disclosures, including entities that:

l are registered in the Australian Business Register and are not a complying superannuation fund, a DGR, registered charity or government entity; and

l have one or more tax debts totalling at least $100,000 that are overdue for more than 90 days, disregarding:

– tax debts where the entity has an arrangement to pay the ATO by instalments (i.e., via a payment plan);

– tax debts subject to an application for release on grounds of hardship; and/or

– tax debts subject to dispute via an objection, AAT or Federal Court review that has not been finalised.

Additionally, the Declaration does not allow debt disclosure for taxpayers who have an active complaint concerning the disclosure of tax debt information that is, or could be, the subject of an Inspector-General of Taxation (‘IGOT’) investigation.

Importantly, if there is such a complaint, the ATO can only proceed with a disclosure of the debt where it is not aware of it after taking reasonable steps to confirm whether the IGOT has such a complaint.

Ref: Taxation Administration (Tax Debt Information Disclosure) Declaration 2019

MYEFO – 2019/20

Treasury has released its Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (‘MYEFO’) for 2019/20 forecasting a surplus of approximately $5 billion.

Proposed new record-keeping course

One new tax-related measure of note in the MYEFO was the announcement the ATO would be provided with a new discretion to direct taxpayers (found to be lacking in their substantiation efforts under audit) to undertake an approved record-keeping course, instead of applying financial penalties.

This is yet another measure designed to tackle the ‘black’ or ‘cash’ economy.

Specifically, the Commissioner will be given the discretion to direct taxpayers to undertake the course where he reasonably believes there has been a failure by the taxpayer to comply with their reporting obligations.

The Commissioner will not apply this discretion to those who disengage with the tax system or who deliberately avoid their record-keeping obligations.

Editor: Such a proposal raises obvious concerns as to the onerous nature of having to comply with such a course, particularly for small business owners whose main priority is to run their business.

Interestingly, there is a precedent for similar ATO directions to taxpayers (i.e., to undertake an approved course), with legislation passed earlier this year allowing the Commissioner to require employers to undertake a superannuation guarantee obligations course where there has been a failure by an employer to comply with those obligations.

New ‘gig’ economy reporting

Additionally, the MYEFO also announced the Government’s intention to implement a new third party reporting regime for the sharing economy.

This will apply to businesses who operate via online platforms within the ‘sharing’ or ‘gig’ economy (e.g., Uber and Airbnb).

It is proposed to be introduced in two stages, starting from 1 July 2022 (for ride-sharing and accommodation platforms) and from 1 July 2023 (for asset sharing, food delivery and tasking-based platforms).

The online platforms will be required to report identification and income information for all its participating members (i.e., both the sellers and providers).

These reports will go directly to the ATO for data-matching (i.e., review and audit) purposes.

Ref: MYEFO 2019/20

The ATO’s Bushfire crisis response

In response to the devastating bushfires across large parts of Australia, the ATO has been keen to advise those impacted that it understands peoples priority is their family and community.

If taxpayers live in one of the identified impacted postcodes, the ATO will automatically defer any lodgments or payments, meaning that income tax, activity statement, SMSF and FBT lodgments (and their associated payments) are deferred until 28 May 2020.

For those affected not in the current ATO postcodes list, assistance can still be provided, with impacted taxpayers encouraged to phone the ATO’s Emergency Support Infoline on 1800 806 218.

Editor: Please contact our office if you have been impacted by this or another disaster for assistance. Ref: ATO website, 20 January 2020 and ATO media release, 20 January 2020.

Please Note: Many of the comments in this publication are general in nature and anyone intending to apply the information to practical circumstances should seek professional advice to independently verify their interpretation and the information’s applicability to their particular circumstances.

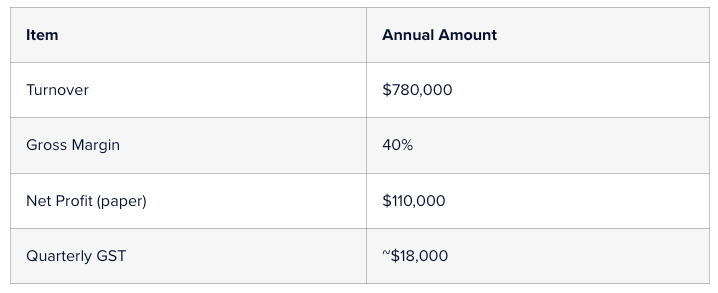

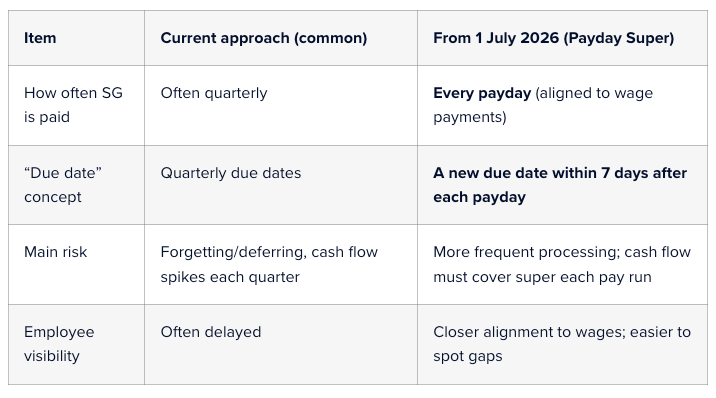

Readiness strategies in preparation for the Payday Super If you run a small business, paying Superannuation can feel like “one more admin job” on top of payroll, BAS and everything else. Two key changes mean Superannuation deserves a fresh look this year: The Super Guarantee (SG) rate is 12% for 1 July 2025 to 30 June 2026 (and remains 12% after that). From 1 July 2026, “Payday Super” starts — employers will be required to pay SG on payday , rather than quarterly, and contributions must be paid into the employee’s fund within 7 days of payday . What does SG at 12% mean in everyday terms? SG is calculated on an employee’s Ordinary Time Earnings (OTE) (often the base rate and ordinary hours, plus certain loadings/allowances depending on how they’re paid). The key point for most businesses is that the Superannuation cost is now 12 cents for every $1 of OTE. If you haven’t already, it’s worth confirming whether your staff packages are “plus super” (super on top) or “inclusive of super” (rare, but it happens). A small misunderstanding here can quietly create underpayments. What is “Payday Super” and why is it changing? Many employers pay the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) quarterly. Payday Super changes the rhythm: From 1 July 2026 , each time you pay OTE to an employee, it creates a new super payment obligation for that payday. You’ll have a 7-day due date for the SG to arrive in the employee’s fund after each payday (this is designed to allow time for payment processing). The ATO is implementing the change, and guidance is already being published to help employers prepare. This reform is aimed at reducing unpaid super and making it easier for workers to see whether super has actually been paid, closer to when they’re paid wages. Quarterly vs payday Super

A real-world case study on trust distributions Mark and Lisa had what most people would describe as a “pretty standard” setup. They ran a successful family business through a discretionary trust. The trust had been in place for years, established when the business was small and cash was tight. Over time, the business grew, profits improved, and the trust started distributing decent amounts of income each year. The tax returns were lodged. Nobody had ever had a problem with the ATO. So naturally, they assumed everything was fine. This is where the story starts to get interesting. Year one: the harmless decision In a good year, the business made about $280,000. It was suggested that some income be distributed to Mark and Lisa’s two adult children, Josh and Emily. Both were over 18, both were studying, and neither earned much income. On paper, it made sense. Josh received $40,000. Emily received $40,000. The rest was split between Mark, Lisa, and a company beneficiary. The tax bill went down. Everyone was happy. But here’s the first quiet detail that mattered later. Josh and Emily never actually received the money. No bank transfer. No separate accounts. No conversations about what they wanted to do with it. The trust kept the funds in its main business account and used them to pay suppliers and reduce debt. At the time, nobody thought twice. “It’s still family money.” “They can access it if they need it.” “We’ll square it up later.” These are very common thoughts. And this is exactly where risk quietly begins. Year two: things get a little more complicated The next year was even better. They used a bucket company to cap tax at the company rate. Again, a common and legitimate strategy when used properly. So the trust distributed $200,000 to the company. No cash moved. It was recorded as an unpaid present entitlement. The idea was that the company would get paid later, when cash flow allowed. Meanwhile, the trust needed funds to buy new equipment and cover a short-term cash squeeze. The trust borrowed money from the company. There was a loan agreement. Interest was charged. Everything looked tidy on paper. From the outside, it all seemed sensible. But economically, nothing really changed. The trust made money. The trust kept using the money. The same people controlled everything. The bucket company never actually used the funds for its own business or investments. This detail becomes important later. Year three: circular money without anyone realising By year three, things had become routine. Distributions were made to the kids again. The bucket company received another entitlement. Loans were adjusted at year-end through journal entries. What is really happening is a circular flow. Money was being allocated to beneficiaries, then effectively coming back to the trust, either because it was never paid out or because it was loaned back almost immediately. No one was trying to hide anything. No one thought they were doing the wrong thing. They were just following what they’d always done. This is how section 100A issues usually arise. Slowly, quietly, and without any single dramatic mistake.